Breastfeeding is a biological process that occurs naturally, but that doesn’t mean it’s easy. Whether because of individual lactation issues, poor nutrition, or infant health issues, there have always been families who have struggled to make breastfeeding work.

Evidence of the use of wet nurses, animal milk, and plant-based milk substitute use from as early as 2000 BC prove that humans have been trying to find creative breastfeeding workarounds for thousands of years. As scientific knowledge advanced, inventors began looking for ways to assist rather than replace a breastfeeding parent.

In the U.S., the first patents for manual breast pumps were granted in the mid-1800s. At the time, they were almost exclusively used for people with inverted nipples or premature, medically fragile infants. While these developments were promising, advancements in infant formula production (and the associated aggressive advertising campaigns) dramatically slowed investment in breast pump research and experimentation.

In the last 30 years, however, research has categorically proven that breast milk delivers nutritional value that best supports growing babies. It took the marketplace a little while to catch up to the research, but now you can find almost as many varieties of breast pumps as you can formula.

When deciding which pump will work for you, it’s helpful to understand how pumps work.

Pumping is possible thanks to the physics governing vacuums. Like a baby with a good latch, breast pumps use funnels tightly sealed around the areola to create a vacuum cycle. This suction exerts negative pressure on the nipples, and by extension, the milk ducts, to pull milk out of the breast.

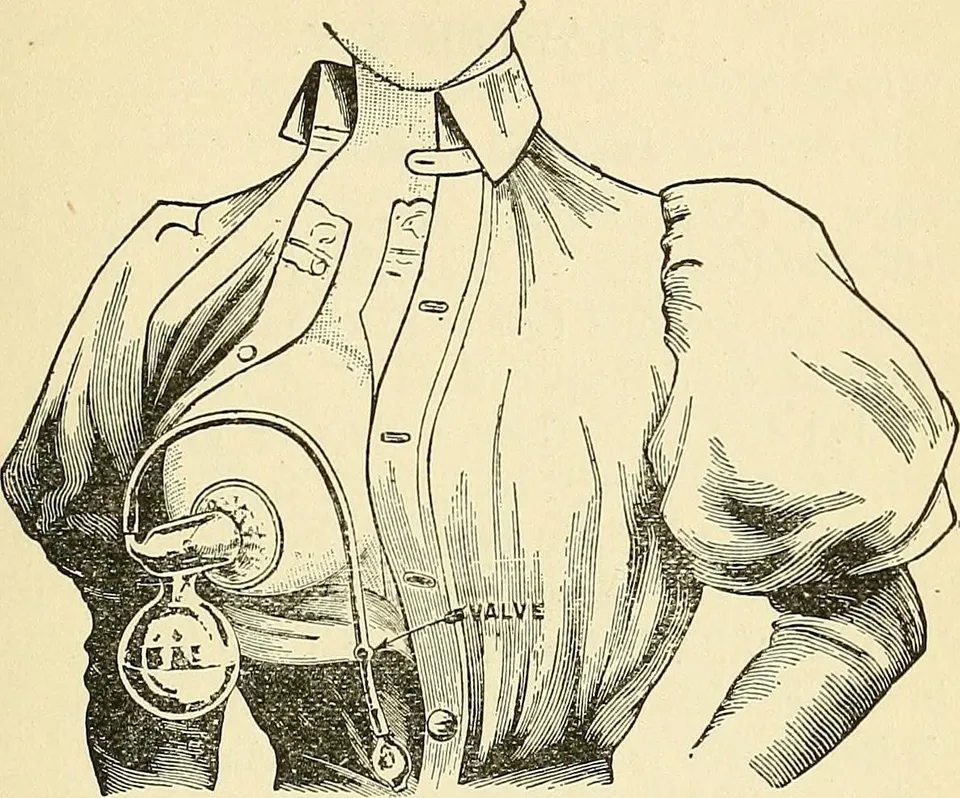

Early breast pump (Internet Archive Book Images)

Early breast pumps were unwieldy and uncomfortable. Suction was immediate and intense, glass flanges restricted milk ducts, cycle speeds weren’t variable, and the units were big, fragile, or both. Vacuum technology pioneers, including Joseph Hoover of Hoover vacuum fame, worked for over 100 years to increase the comfort, ease-of-use, portability, and effectiveness of breast pumps.

Breast pumps today vary mechanically, but they all have the same basic construction:

The pump motor, which sits in the housing of your devices, takes in and displaces air to create the vacuum, or suction, effect that pulls milk out of the breast.

The diaphragm separates the “wet” and “dry” parts of the pump, which keeps expressed milk from entering the motor or tubing. Diaphragms create a “closed system” pump, which is recommended for preventing bacterial growth that can contaminate your pumped milk supply.

The breast shield is the only piece that connects to you and your pump. A cone- or funnel-shaped piece of plastic or silicone, the breast shield goes over your nipple and areola while attached to the vacuum function by flexible tubing. The breast shield is also usually screwed onto a bottle or other container so breast milk can be collected.

Valves attach to the underside of the breast shield. They usually have a small, silicone membrane at the end that flexes and releases with suction. The membranes are soft and loose enough that expressed milk can flow between them and the valve while remaining strong enough to create negative pressure.

The flexible tubing may look unimportant, but it’s actually one of the most important parts of your pump. Similar to the physics of a straw, the air displaced by motor movement moves back and forth through the tubing to the breast shield, mimicking the sucking motion of your baby.

Most pumps have a bottle or similar container that either snaps or screws onto the breast shield. These containers are usually compatible with bottle collars and nipples, which means they can pull double duty for milk collection and feeding time.

Babies’ immature immune systems are susceptible to illness and infection—that’s why new parents have a justifiable reputation as germaphobes. Bacteria that likely wouldn’t affect you or your seven-year-old can cause your newborn all kinds of trouble.

Keeping your breast pump clean and in working order is an easy way to protect your baby from unnecessary exposure to dangerous bacteria.

The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) has guidelines and FAQs for the cleaning and care of breast pumps that provide responsible and realistic tips for maintaining your breast pump safely. These common-sense tips include:

Sanitizing your pump, either in the dishwasher or boiling water, can be done every few weeks. But remember, regular cleaning is more important and beneficial than infrequent sterilization.

You wouldn’t cook with mildewy pans or broken wooden spoons, and you shouldn’t pump with moldy or damaged pumps. Additionally, worn-out pump parts are inefficient and can significantly contribute to reduced milk supply. Here are a few things to keep in mind for successful pumping:

Nest Collaborative’s team of International Board-Certified Lactation Consultants (IBCLC) are committed to providing excellent prenatal and postpartum lactation support to all parents.

We can help you feel more comfortable and confident in your ability to breastfeed successfully in the comfort of your own home and the convenience of your schedule. If you’re struggling with pumping, don’t hesitate to reach out to our team of experts at Nest Collaborative.